Συνέντευξη του Michael Soth

στην Εναλλακτική Δράση, 2019

Michael, why do we need companionship? Is it an innate need or just something we learned from society and we are trying to reproduce it?

It does seem that the need for companionship is deeply hardwired into human biology - after all, we are a species of mammal where as newborns we are dependent on our social environment, our parents and elders for an extraordinarily long time. As interpersonal neurobiology teaches us, we are deeply social animals, and our identity is socially constructed. According to affective neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp, our brains have seven innate circuits and systems (see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=65e2qScV_K8), some of which are designed to establish and facilitate our bonding with other humans.

It was John Bowlby (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3LM0nE81mIE) who studied human attachment and what can go wrong with it in early child development, and put it on the map in psychology, psychoanalysis and health care. Where Freud thought humans were instinct-driven and pleasure-seeking, from the 1950s onwards there was a philosophical shift to thinking about humans as object-seeking (Fairbairn), which later led to the idea of primary intersubjectivity ( i.e. that humans recognise each other from birth as interrelated subjects with agency and impact on each other - see Colwyn Trevarthen: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pW42_wYNGWk). On the other hand, solitude and its blessings are vastly underrated, especially as we get older (there is a book by well-known Jungian author Anthony Storr on that topic).

But the deeper question is: what kind of connection do we have with others? Is our connection with others an expression of our innate needs? Some of the ways in which we try to connect with others are profoundly addictive, co-dependent and actually an escape from intimacy. So in that case, others become a tool that we use to compensate for our woundedness and distract ourselves from our vulnerability. In that case, companionship is not characterised by love or driven by affection, but by entitlement to having our needs met and using others as objects and means of gratification.

In the West, we are living in an age of narcissism epidemic, with the result that our innate needs for connection with others are buried and hidden under layers and layers of disconnection, defences and addictions, i.e. relationships as a fake substitute for innate needs. So in that kind of cultural atmosphere - where the human heart is starving in front of a buffet of apparent abundance - people's attempts at companionship may well be heavily shaped by social norms and social media. But as long as you don't mistake Facebook likes for companionship, or narcissistic adoration for love, the innate need for companionship is quite visible and transparent. The human soul and its longing for love and true connection is indestructible and will continue seeking ways of turning the most vacuous celebrity circus into a journey of the heart and the most contorted and neglected desert into a garden full of roses.

2. Are there some distinct stages that interpersonal relationships go through? If so, can you summarise them?

In an 'ideal' world, relationships start with ‘falling in love’. By ‘falling in love’, relationships start in an 'ideal' world. However, as many wise people have said, falling is easy, any idiot can fall in love. The tricky and laborious thing is learning to love, the nitty-gritty everyday capacity for loving, for loving the other as they are (rather than squeezing and nudging and pressurising them into a mould of who we need them to be).

So one way of describing the journey toward mature relationship is from the blindness of falling in love towards taking responsibility for loving. And the question then shifts from "do you love me?" to "do you feel loved by me?" (there is a beautiful book with that title by my late colleague Philip Rogers). Along that journey, one of the most crucial phases that a couple goes through is the disappointment of the initial idealisation: we realise that the other is not the god or goddess which we fell in love with, who will complement us perfectly and make the rest of our lives effortlessly happy. On the contrary, the other's mysterious otherness - which we found initially so compelling and attractive - easily turns into a challenge, then into friction and often into aggravation.

Among couple therapists, a well-known principle is: 'you either develop it, or you marry it'; that is to say: whatever qualities or faculties I feel made whole by through the other, eventually I am confronted with the challenge of finding and developing these also within myself. That process usually involves some friction between the couple, and letting go of the initial – usually unconscious - ‘deal’ between them when they first got together. Generally speaking, our culture seems to lack the psychological understanding that friction in a couple has a developmental function - it's meant to build our character, or as Jung said, it's part of our individuation process. The other is the grit in the oyster that is meant to develop the pearl of our Self. That means there is a larger purpose to couples fighting and struggling, and an important part of deep couple therapy is to help the partners discover that larger purpose.

In most relationships, love is hampered by long-established habits and patterns, most of which go back to childhood experiences of love or lack of love, and different degrees of insecure or avoidant attachment. A simple image for this is that we carry around with us a defensive armour - a set of protective mechanisms shielding our heart - which gets in the way of love flowing between the couple.

So there are different stages in a couple's life where we get entangled in these patterns, constantly projecting them onto the other and getting triggered by the other - and hopefully we get the support and help to work these patterns and defences through. So couples go through stages of realising that they are each carrying childhood wounds, family wounds, cultural wounds - that it is not two individuals, but two families that get married - and that the defences against these wounds shape the atmosphere of our home. We carry the ancestors with us and they crowd the home and the bedroom. Esther Perel, one of the foremost couple therapists on the planet, says she's had three marriages in her life - to the same person. So there are definitely distinct stages of our couple relationships which we can be seen to go through and which correspond to the stages of our life journey.

3. In the description of your seminar I read with surprise that “one of the purposes / side-effects of the relationship is to destroy each other’s defences”. Can you elaborate?

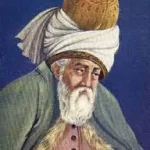

For many of us, the only thing that motivates us sufficiently for the hard labour of confronting our own defences is a loving relationship. Most of the time, many of us take these defences for granted as just who we are, as part of our identity. But they are a barrier to development, maturation and compassion, like a glass cover around the heart. There is a beautiful Rumi poem "Shadow and Light Source Both" where he says:

"What hurts you, blesses you.

Darkness is your candle.

Your boundaries are your quest.

I could explain this,

but it will break the glass cover around your heart

and there's no fixing that.

You must have shadow and light source both.

Listen, and lay your head under the tree of awe."

So there is a deep logic to lovers destroying that glass cover around each other's heart. Couples run into each other's defences like knights throwing themselves on the outstretched sword of the other. We should be angry with each other's defences - even if we battle the other's defences for our own very personal and partial reasons, there is nevertheless method to the madness, a point to the fighting, a teleology to the endless circles of bickering and attrition.

4. Michael, according to your experience, what are the reasons why many people prefer to stay in a existing relationship that doesn’t offer anything any more, rather than set a new course and go for a better relationship?

Based on everything I said above, when people in relationships come to the end of their tether, and have been hurt too many times, and when their frustration and hatred with the other outweighs the love and affection, their minds come up with all kinds of explanations and rationalisations: "s/he is not the same person I fell in love with - they have changed!" "it turns out we were incompatible all along!" "we have developed differently, and have nothing in common any more!"

But usually, these thoughts are just the superficial symptoms of the escape impulses away from the crisis, in general terms usually the crisis of disappointment: from the other being a balm for the soul they have turned into more salt into the wound. These thoughts and escape impulses are very understandable - but that doesn't mean they are valid, realistic, or reliable, or that they signify a proper ending of the relationship. To the couples therapist, looking in neutrally from the outside, it's usually obvious that both partners are running away from themselves and from the urgent lessons that need to be learned.

In many situations, if people split at that point, they just repeat the same thing with the next partner they are running towards. Even when the couple have decided to separate, there is still some point in couple therapy sessions, in order to get some help in learning the lessons from the relationship that is just breaking down, so the same patterns and dynamics won't be repeated in the next one. In many couple situations, it is not at all clear-cut and obvious whether the impulse to separate is a healthy and mature desire to move on to something better, or a blind escape that will only lead from jumping from the frying pan into the fire.

Using couple therapy to work through the lessons of a relationship crisis and the breakdown of love is usually not a simple thing that can be done in a few sessions. But sometimes, the darkest hour is just before the dawn, and mature loving can emerge like a phoenix out of the ashes of hatred. It is true that most couples come too late to therapy, many years after they should have asked for help, and only reach for couple therapy when disappointment, frustration and hostility are deeply entrenched. But the decision whether to set a new course within the existing relationship, or whether to set a new course towards a new relationship, depends a lot on the support and resources and psychological wisdom that a couple in crisis can draw upon. After all, a few couple therapy sessions cost a fraction of what most couples easily spend in a divorce case.

5. Many times I have wondered in my life: am I falling in love with the person that I see in front of me or the longings and expectations that this person is producing in me? Am I falling in love with the other or an imaginary part of myself? Is there a way to distinguish one case from the other?

The therapeutic approach that has accumulated most wisdom on this question are the Jungians. Traditionally, they have assumed that a man falls in love with his 'anima', and a woman falls in love with her 'animus'. These ideas have been heavily questioned, as they should be, because of their underlying patriarchal and heterosexist assumptions; and many people are refuting these ideas as outdated and reactionary.

But we may be chucking out the baby with the bathwater if we do this. There may be ways in which we can salvage something helpful and precious from the ideas of that therapeutic tradition, that can help us in our loving. Whether we are men or women, and whatever our sexual orientation and identity, anybody who has even minimally followed their dreams, will realise that our dreamworld is populated by images of feminine and masculine figures which do develop over time. Traditionally, Jung speculated that a man slowly develops images of femininity by differentiating these out of his images of mother, both his real mother and his imaginary mother, what Jung called the ‘mother complex’; and the reverse for the woman. But we do not have to restrict these ideas to heterosexist normative assumptions; and, in any case, who is to say that the dreamworld is immune against inheriting patriarchal stereotypes down the generations?

The problem here are not necessarily the therapeutic ideas themselves, but their over-generalisation as universals across time, space and cultures. There is no doubt in my mind that mythical motifs, both from matriarchal and patriarchal times, survive in our dreams and influence our pre-conscious imagination. These images are emotionally charged - Jungians call them 'numinous', i.e. spiritually charged - and they can strongly influence our waking actions; such images can easily be projected into the world, and attract suitable human targets for us to fall in love with.

Most people in the West assume they are free to fall in love with just about anybody, but the unconscious guides and restricts our choices, and is highly selective. In order to distinguish one 'falling in love' case from another (it almost starts sounding like a Sherlock Holmes story), the first question is not regarding the 'targets' out there, but the nature and quality of the habit of falling in love, i.e. you, yourself and your unconscious. A stereotypical pattern would be somebody who keeps falling in and out of love quickly and frequently, and has intense feelings as long as the conquest is elusive, but loses interest and gets bored and judgemental once the other shows interest and reciprocates - we might call this the Don Juan habit. This is a sure sign that we are not dealing with love, but with imaginary parts both in the other and yourself.

6. Is love enough by itself to keep a relationship going?

The answer to this question rather depends upon what you mean by 'love'. To keep a relationship going, love itself needs to develop as the two partners develop, so we are definitely not talking about any kind of static love, any kind of fixed or guaranteed state that we can hold onto. There is a famous saying by James Hillman that love requires letting go of any fixed image or notion of love. What that implies, conversely, is a kind of curiosity that can only be maintained if we let go of any sense of entitlement to love, any kind of demand that the other owes us love, or is obliged to fulfil their marriage vows. For love to develop, we need to let go of any firm anchoring at the supposedly safe shore, and be curious about the uncertainty of a greater kind of love, that can only happen if we don't grasp for it or cling to it.

Regarding what we mean by 'love': my ego, of course, wants love on my terms, by my definition and parameters and on my understanding. But by definition, that's not love, that's just egotism. The demand for love on my terms is usually a 'frozen need' - a childhood wounding fixed in time, demanding from our partner what we failed to receive many years ago.The Greeks knew that the mighty river of love is made up of different tributaries, and so they had five different words for different kinds of loving:

Desire – Attraction (epithumia)

Longing – Romance (eros)

Belonging – Affection (storge)

Cherishing – Friendship (phile)

Selfless Giving – Compassion Love (agape)

To sustain love in an ongoing relationship, it probably needs all five, in different combinations over time.

7. In your opinion, what is the biggest mistake that therapists and mental health professionals make when approaching couple therapy?

For the workshop, I am distinguishing eight different kinds of couple therapy - this is not a precise categorisation, but just some rough and ready broad brush stroke outline, in order for us to appreciate the different assumptions, theories and techniques and their diverse underlying philosophies.

Most couple therapy is too simplistic and didactic, as if the main thing that couples need is to be taught how to communicate correctly (i.e. how to become more rational and reasonable people with each other). These kinds of couple therapy do not appreciate the power and force of the unconscious, and they certainly do not see a deeper purpose to the fighting. These kinds of couple therapist fancy themselves as some kind of enlightened expert guide, and sometimes they are wise elders.

However, as in all therapy, therapy works faster, better, and more comprehensively, with a wider range of clients when the therapist can be integrated and flexible in their stance, wondering about the advantages and disadvantages of the particular relational stance they are taking or the relational role they are being given by the client (or in the case of a couple: the two clients).

Although the attempt to integrate different therapeutic approaches is not at all straightforward and has its own complications, an integrative therapist always has one key advantage: and inherent non-dogmatic flexibility and willingness to adapt to the person in front of them. They say that to somebody with a hammer, everything looks like a nail; a therapist with a single therapeutic approach will try to apply that to just about everybody who comes along.

In the realm of couple therapy, non-dogmatic integrative openness is still some way off in the future.

8. You talk about embodied couple therapy - what is that and how does it work? What does an embodied approach have to offer in addition to the talking therapies for couples?

Although the idea of embodiment has become very fashionable in psychotherapy over the last 20 years, working with the body has remained fairly clinical and superficial. Too often, it has been reduced to just another technique, as just another gimmick when the client is resistant to talking therapy. A deep understanding of the body-mind connection is only present in a small minority of therapeutic traditions, through somatic psychology, body psychotherapy based in the Reichian tradition and more recently somatic trauma therapies deriving from that tradition.

Modern neuroscience has deconstructed the 19th-century idea of mind-over-body (taken for granted by Freud and enshrined in psychoanalytic thinking down the generations), but hasn't got to the point of translating that into embodied ways of working, both relationally and in terms of technique (see a review of the latest thinking in neuroscience, as presented by Allan Schore). For the purposes of couple therapy, embodiment enters as a significant feature because so many of the destructive cycles that couples get into are perpetuated through non-verbal communication, precisely because the partners are attached to each other and know each other so well. Theoretically, some approaches to couple therapy are trying to understand this in terms of each partner's attachment pattern, which are rooted in pre-verbal attachment experiences (and right-brain-to-right-brain attunement).

In simple terms: most of our 'working models' for intimacy and love were developed before we had a separate, individual mind and therefore these blueprints for bonding and relating are stored in implicit body memory. These implicit patterns are activated years later when people attach to each other in intimate, committed relationships; we could also say that much of the unconscious is tangible and present and active in subliminal and non-verbal communications which the partners are not conscious of and cannot give a verbal account of. That explains why much couple therapy when it restricts itself to talking is limited and inefficient - left-brain reflection and language usually hasn't even got into the starting blocks by the time that the right-brain has already got agitated, emotional and reactive.

In embodied couple therapy, the embodied couple therapist uses their own bodymind to plug into, and insert themselves as a catalyst, in these kinds of subliminal exchanges. That may include inviting the couple to get out of their chairs, take certain stances or positions, move around the room, or enact physically internal and external figures that make projections and projective identifications explicit through the bodies.

9. Is learning about couple work useful only to couple therapists?

We could distinguish psychological work on our capacity to form and maintain relationships from couple work (which can often happen in groups and workshops), from explicit teaching for couple therapists, on how to do it.

My experience of working with couples is that our culture is generally speaking psychologically naïve about what happens in intimate relationships, the dangers and threats of love and how we defend and protect ourselves against it, and why we are therefore not ready for the loving relationship that many of us so desperately seek.

These days, quite a lot of therapy involves ‘dating coaching’ - clients are desperate for some kind of help and understanding in finding partners, and especially suitable partners. There are all kinds of dreadful pseudo-experts available on YouTube, catering for the desperate with all kinds of snake oil, especially warning them about hooking up with dangerous partners with all kinds of psychological pathologies. In this kind of climate, many people would benefit from some kind of psychological depth understanding - it is not really fair to expect anybody else to love me unless I have at least a modicum of loving myself. Many of us need help to find that, as many of us live in various degrees of self-loathing (there is, for example, an epidemic of young women who hate their bodies, which makes genuinely loving intimate relationships quite difficult). Workshops for couples, where couples can share with other couples their pain and struggles, are definitely helpful and useful, and I predict that we will see a whole lot more of them in the future. These kinds of workshops would benefit enormously from being led by facilitators who can integrate the various approaches and paradigms of couple work. For therapists to grow and develop towards that kind of integrative capacity, I'm offering this workshop in Athens as a learning space, where therapists can experiment with expanding their individual work into the more complicated and complex work with couples. This workshop is therefore restricted to practising therapists.

Σεμινάρια με τον Michael Soth

Επισκεφτείτε here για να δείτε τα επερχόμενα σεμινάρια με τον Michael Soth